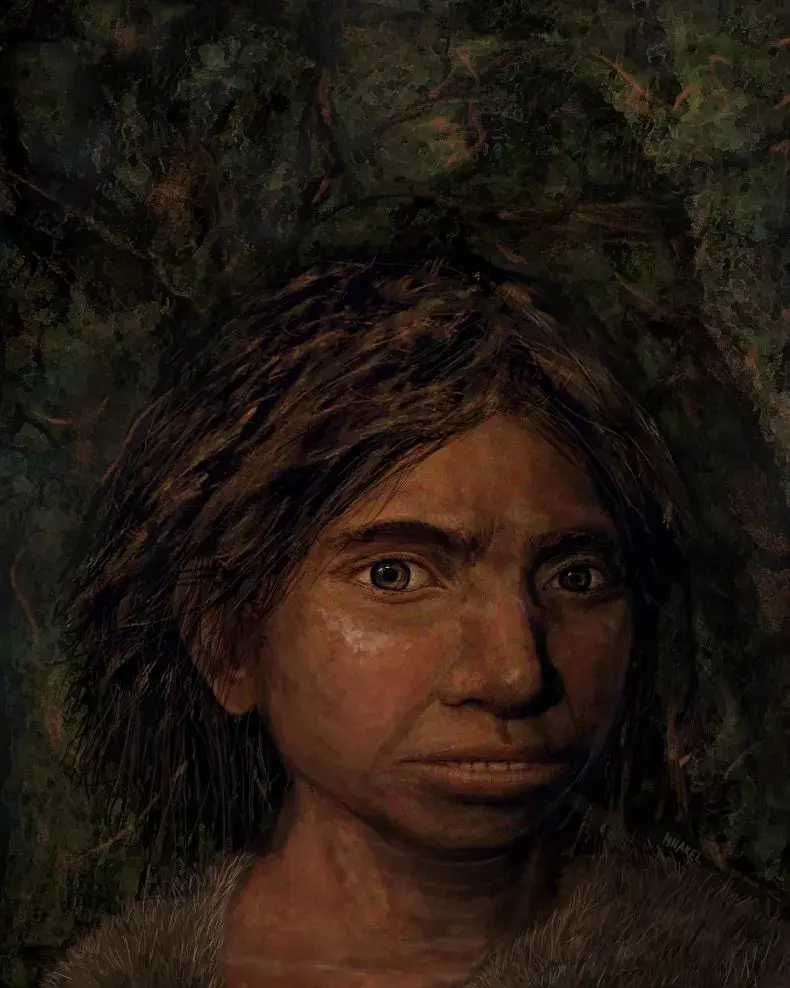

Ancient DNA puts a face on the mysterious Denisovans, extinct cousins of Neanderthals

Researchers have been able to bring the now-extinct cousins of Homo sapiens, the Denisovans, back to life (of sorts)—offering us the first glimpse at what these little-understood hominids would have looked like tens of thousands of years after they went extinct.

Up until now, palaeontologists have faced a major problem. This being that all that remains of the ancient species are a few teeth, jawbone, and a pinky bone.

But researchers at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem writing in the journal Cell have side-stepped this problem by analyzing methylation in their DNA.

The result is the first ever reconstruction of a Denisovan.

“We provide the first reconstruction of the skeletal anatomy of Denisovans,” said author Liran Carmel, from the Department of Genetics at Hebrew University of Jerusalem in Israel.

“In many ways, Denisovans resembled Neanderthals, but in some traits, they resembled us, and in others they were unique.”

Indeed, researchers identified 56 anatomical features that distinguished Denisovans from both modern humans and Neanderthals.

The bulk of those (36) were in the skull—the reconstruction suggests a Denisovan skull was wider and they had a longer dental arch.

As far as similarities go, the researchers believe the Denisovans had an elongated face and a wide pelvis—like Neanderthals, who they separated from sometime between 390-440,000 years ago.

Their ancestors split from ours 520-630,000 years ago but recent studies have shown that up to six percent of DNA in present-day Melanesians and Aboriginal Australians can be traced to the Denisovans. East Asians, Native Americans and Polynesians also share Denisovan DNA but to a lesser degree.

This reconstruction was only possible because of a technique that uses genetic data to predict the skull structure. Specifically, gene activity patterns associated with DNA methylation.

These are chemical changes that affect gene activity but do not change the underlying genetic sequence of As, Gs, Ts and Cs.

The team compared patterns of DNA methylation in three hominid groups to work out where exactly the patterns differed and then, compared how any differences might affect anatomical features. To do this, they sought out human disorders where those genes are damaged and their function removed.

The process allowed Carmel et al to predict how the activity of different genes affects the appearance of the skeleton — and in what direction it would change. For example, would this particular gene activity result in a shorter or longer femur?

The researchers tested the strength of their technique by looking at two primate species that are already known, the Neanderthal and the Chimpanzee.

The efficiency of the prediction when it came to reconstructing traits separating modern humans and Neanderthals was 83 percent, with an 88 percent success rate at predicting their direction of change.

It was slightly better at differentiating between modern humans and chimpanzees, reaching 91 percent precision at predicting divergent traits and 91 percent precision at predicting their direction.

Interestingly, during the review process, a paper on the first Denisovan mandible discovered was published — and it matched up with their predictions based on the DNA methylation maps.

“Studying Denisovan anatomy can teach us about human adaptation, evolutionary constraints, development, gene-environment interactions, and disease dynamics,” said Carmel.

But it has implications beyond Denisovans and human evolution.

“At a more general level, this work is a step towards being able to infer an individual’s anatomy based on their DNA, ” he added.

Tom Higham, a professor of archaeological science and Director of the Oxford Radiocarbon Accelerator Unit at Oxford University not involved in the study, called the method attractive and the results exciting.

“The genetic data being used for Denisovans is very limited, because only one high coverage genome is available currently,” Higham told ArchaeologyWorldNews. “

Nevertheless, the authors make a strong case with Neanderthals and chimpanzees that they can predict appearance with a high level of confidence.

“The new paper is very interesting and with the discovery of new fossil and more genomes, sharper predictions based upon DNA methylation maps will be possible. There will be exciting opportunities to test the method when new fossil finds and genetic analysis of them are published, hopefully in the near future.”