A cave in Argentina houses the oldest known pigment-based rock art in South America

A curious comb drawing discovered in the Huenul Cave in Argentina may be the oldest rock art ever uncovered in South America.

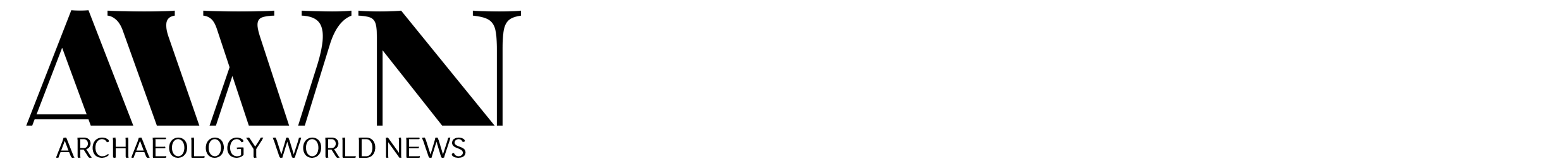

The Huenul Cave, a 630-square-meter rock shelter located in northern Patagonia, has been a site of human interest for millennia. The cave’s interior is adorned with approximately 900 unique ancient paintings featuring an array of geometric patterns, human figures, and animal depictions.

Patagonia, situated at the southernmost point of South America, was first inhabited approximately 12,000 years ago by early settlers. However, about 10,000 years ago, the region began to experience increased aridity which made survival challenging.

Archaeological evidence found in local caves indicates that these sites were likely abandoned during this period due to the harsh environmental conditions.

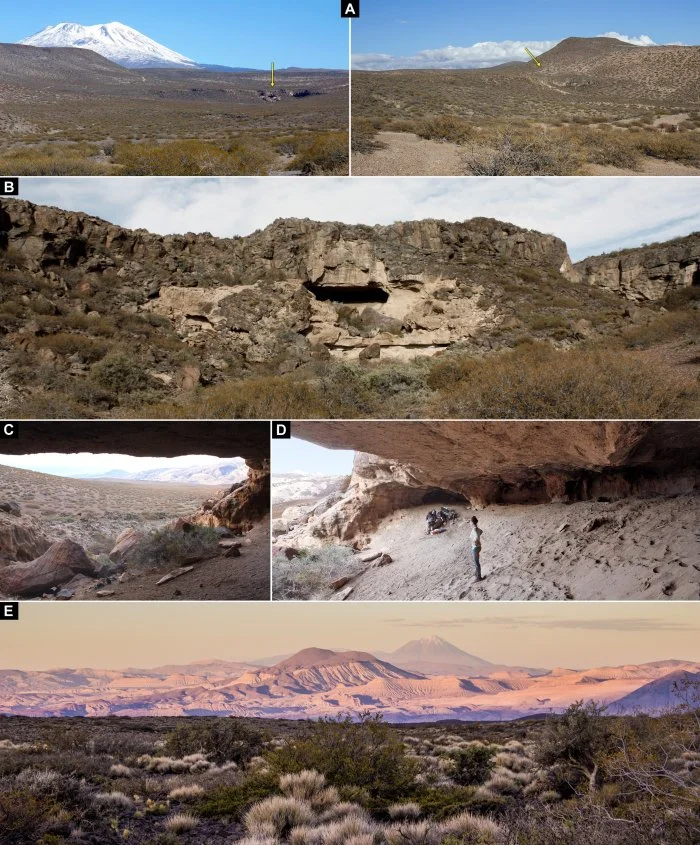

While conducting an analysis of rock art, Guadalupe Romero Villanueva, an esteemed archaeologist at Argentina’s National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET), observed that certain paintings within the Huenul Cave appeared to predate others.

According to a recent study published in Science Advances Villanueva and his team of researchers discovered a puzzling comb-like pattern that dates back approximately 8,200 years.

“That makes the motif—shaped like a downward-facing comb with four teeth—the oldest directly dated rock art painting in South America.

Dates from similar motifs in the cave span the subsequent 3000 years, implying people visited the cave repeatedly and continued the artistic tradition for many generations,” the researchers write in their study.

“Now, we have precise chronology with which we can begin to model the colonization of this area,” says University of Buenos Aires archaeologist Luis Borrero, who was not part of the research team. “It’s quite interesting and absolutely new.”

The surroundings of Huenul Cave present a challenging environment, with human survival there remaining uncertain even in the present day.

The cave is situated on a desert plain at an elevation of 1000 meters above sea level, receiving a mere 5 centimeters of annual rainfall. A significant distance of 10 kilometers separates the expansive, north-facing entrance of the cave from the closest water source.

When the comb motifs were painted, climate records suggest conditions were even harsher. “The south of South America was one of the last places to be settled by humans. This is the end of the trail,” Borrero says. “It’s a place where you cannot make mistakes. If you are lost, it’s forever.”

The revised dates reveal that despite enduring harsh, prolonged periods of drought, people repeatedly visited the cave. It was likely used as a sacred site or gathering spot.

The team discovered an array of artifacts within the cave, including ornate guanaco bones, minuscule shell beads, and branches tinted with red ochre. However, there’s no evidence to suggest that anyone resided in or spent a considerable amount of time in the cave.

The researchers suggest “small bands trekked across the desert to the site periodically to make cave paintings, perhaps as a way to knit together far-flung groups.”

“It continued to be visited in a period where you wouldn’t expect people to go to an extreme desert landscape,” Romero Villanueva says. “During hard times they continued to visit this place and maintain ties.”

Although the comb drawing currently acts as a historical account of past approaches to climate change issues, the significance and intent behind the motif remain unclear.

The study is published in the journal Science Advances