40,000-Year-Old Multi-Compound Glue Suggests Neanderthals Were Smarter Than We Thought

Researchers have discovered stone tools bound together by a multi-component adhesive, providing further substantiation of the intellectual capacity of Neanderthals.

These artifacts represent the oldest known evidence of a complex adhesive in Europe, implying that these precursors to contemporary humans exhibited a more advanced level of cognitive ability and cultural evolution than previously thought.

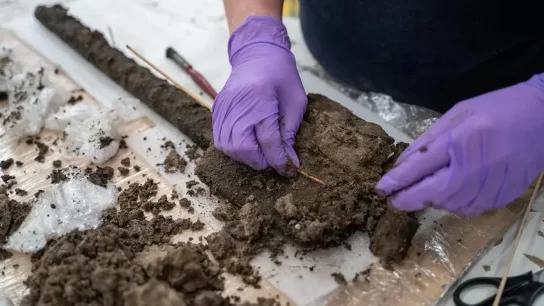

A team of researchers from New York University, the University of Tübingen, and the National Museums in Berlin have taken a closer look at stone tools from Le Moustier. These tools were used by Neanderthals during the Middle Paleolithic period, specifically the Mousterian era between 120,000 and 40,000 years ago.

These artifacts are part of Berlin’s Museum of Prehistory and Early History collection but hadn’t been thoroughly examined before.

Interestingly, these tools were rediscovered during an internal review of the collection, and their scientific significance was finally acknowledged.

“These astonishingly well-preserved tools showcase a technical solution broadly similar to examples of tools made by early modern humans in Africa, but the exact recipe reflects a Neanderthal ‘spin,’ which is the production of grips for handheld tools,” says Radu Iovita, an associate professor at New York University’s Center for the Study of Human Origins.

Dutkiewicz points out that the items were meticulously wrapped one by one and have remained untouched since the 1960s. Consequently, any organic residue stuck to them has been remarkably well-preserved.

The researchers discovered remnants of a blend of ocher and bitumen on various stone tools, including scrapers, flakes, and blades. Ocher is essentially an earth pigment found in nature, while bitumen, a constituent of asphalt, can be derived from crude oil or naturally present in the soil.

“We were surprised that the oche content was more than 50%,” says Patrick Schmidt from the University of Tübingen’s Early Prehistory and Quaternary Ecology section. “This is because air-dried bitumen can be used unaltered as an adhesive, but loses its adhesive properties when such large proportions of ocher are added.”

among other parameters. The concoction had the perfect balance of stickiness – enough for a stone tool to adhere to it and yet not cling onto hands. This made it an ideal substance for crafting handles.

A detailed microscopic analysis of the wear patterns on these stone tools indicates that the adhesives found on the tools from Le Moustier were indeed used in this manner. The application of multi-component adhesives, which include a variety of sticky materials like tree resins and ocher, was previously identified only in early modern humans, Homo sapiens, in Africa. This practice was not known to have been used by earlier European Neanderthals.

“The tools showed two kinds of microscopic wear: one is the typical polish on the sharp edges that is generally caused by working other materials,” explains Iovita, who conducted this analysis.

“The other is a bright polish distributed all over the presumed hand-held part, but not elsewhere, which we interpreted as the results of abrasion from the ocher due to movement of the tool within the grip.”

The creation and application of adhesives in tool production is seen as some of the most compelling proof we have of early humans’ cultural progression and intellectual capacity.

The authors highlight that in the Le Moustier area, gathering ocher and bitumen was a significant task. Due to their remote locations, it required considerable effort, strategic planning, and a focused approach.

“Compound adhesives are considered to be among the first expressions of the modern cognitive processes that are still active today,” says Schmidt.

“What our study shows is that early Homo sapiens in Africa and Neanderthals in Europe had similar thought patterns,” adds Schmidt. “Their adhesive technologies have the same significance for our understanding of human evolution.”

The study was published in the journal Science Advances