Bone tool found in Spain suggests prehistoric tailoring existed 40,000 years ago

Almost 40,000 years ago, some of the earliest modern humans to settle in Spain wanted to strut their stuff in lovely fitted outfits that showed their charms. No throwing some lousy pelts over the shoulder that would make them look fat – that’s so Middle Paleolithic.

This scenario arises from an extraordinary discovery: a tool that may have helped tailor outfits to fit thousands of years before the invention of the needle.

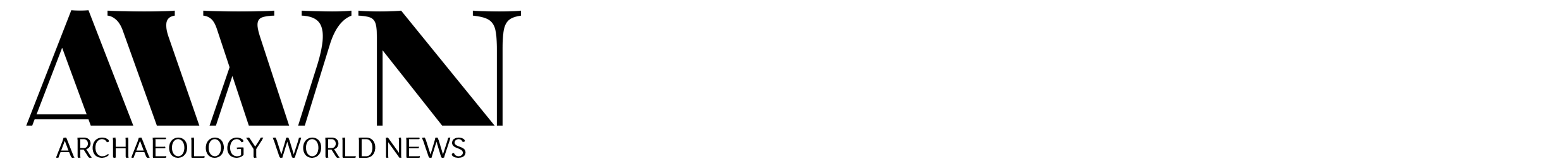

That utensil was a bone fragment from the hip of a herbivore, probably a horse or an aurochs. The researchers could discern uneven puncture marks on the artifact.

And how does the perforated broken hip bone of a horse or ancient cow found in Gavà, Spain, lead us to Upper Paleolithic haute couture? The specimen, which dates to around 39,600 years ago, is discussed in a paper published Wednesday in Science Advances by the Université de Bordeaux’s Luc Doyon and colleagues.

Clothes make the hominin

The artifact was discovered not in some convenient cave but in an open-air site near the delta of a stream that maybe became quite the torrent during heavy rain.

Other finds at Gavà include six stone tools; that is, practically nothing. “Occupation of the site by humans was quite sporadic,” Prof. Doyon says.

In that context, finding the earliest known tool for pre-needle precision tailoring was absolutely miraculous, he adds.

It being an open-air site with few clues, how can we know who made the artifact – the last of the Neanderthals in Spain or the first of the Homo sapiens there?

“Based on the age of the object, and on the other material cultures found in association, it would be Homo sapiens, among the first Homo sapiens to be established in Europe about 40,000 years before the present,” Doyon says.

Clothing is believed to go back over 120,000 years, and even then, spots were in fashion. Early garb seems to have involved skinning dinner (or a cat) and throwing on the pelt.

Artifacts believed to be early needles have been found in South Africa from 61,000 years ago, Siberia’s Denisova Cave from 50,000 years ago and China from 45,000 years ago.

In Spain the technology seems to have arisen 26,000 years ago, Doyon says. Maybe they had needles that haven’t been found yet, but what the researchers found seems to be the next best thing – a punching board for animal hide.

That is, you lay the leather on the board and make holes in it using an awl, or whatever. We know that Neanderthals could make string and the sapiens at Gavà probably had cord technology too. Think how corset stringing works.

Using these techniques, you can create straight seams, Doyon explains. You can make fitted clothing before needles. Try it.

The hyena hypothesis

But how do they know what it is? When you find a modified fossil bone from antiquity, three main hypotheses arise, Doyon says.

Number one is that a hyena or some other fanged animal made the holes. Take the “Neanderthal flute” of Slovenia that some experts surmise was a bone modified by musically inclined hominins, while others suspect it was debris from a cave bear cub’s meal.

In our case, the team verified that the perforations in the hip bone could not have been made by a hyena, bear or other carnivore scavenging the dead herbivore. “Carnivore tooth marks are different,” Doyon says.

Another hypothesis is that the modified bone was simply a form of art, or to record information. Some see holes in a bone, some see a primordial lunar calendar and so on.

“The issue with this hypothesis is that, of the 28 punctures we see on the specimen, only 10 are aligned, and the other 18 are very disorderly and barely visible, some only under the microscope,” Doyon says.

Why make holes to record information if you can’t see the holes? And there was no organized pattern, so this likely wasn’t art.

The researchers could discern that the bone exhibits six events of modification. The holes were made by the same basic technique but using six different tools. This says everything.

Okay. Not art. Six modification events. The next question was what purpose this served, and following experimentation including attempts to pierce latter-day leather using stones and bones, the researchers realized that “we could produce exactly the same type of modifications. So we made our conclusions,” Doyon says.

In their experiments, they reproduced the marks on the 10-centimeter-long (4-inch) bone fragment by using various tools to apply pressure on leather placed over cow ribs.

The researchers even surmise that the humans used burins, a sharp-tipped engraving tool, to puncture the hide, which would mark the underlying bone and ultimately puncture it.

Comparing the reproductions to the artifact, the researchers deduced that groups of punctures must have been made during different sessions.

Some were purposely aligned and equidistant and would have produced holes for stitching leather pieces together.

“The evidence from Canyars [in Spain] indicates that an effective pricking technique was well established in Southern Europe at the onset of the Upper Paleolithic,” the authors write. “We argue that this innovation documents a previously unrecorded tipping point in cultural adaptation favoring modern-human niche expansion.”

Until now it wasn’t clear how clothing had been made, just that (based on studies involving head and body lice) it was made.

“We have a few awls or pointed stone tools here and there, but we basically are still in the dark regarding the techniques to make fitted clothes,” Doyon says. “Now for the first time we’re documenting a technique that’s used by traditional societies and cobblers to this very day.”

Why would they prick their leather on a bone rather than a rock? Well, their piercing thing would last longer and they could make nice linear seams to make sexy tight-fitting horsehide, or whatever.

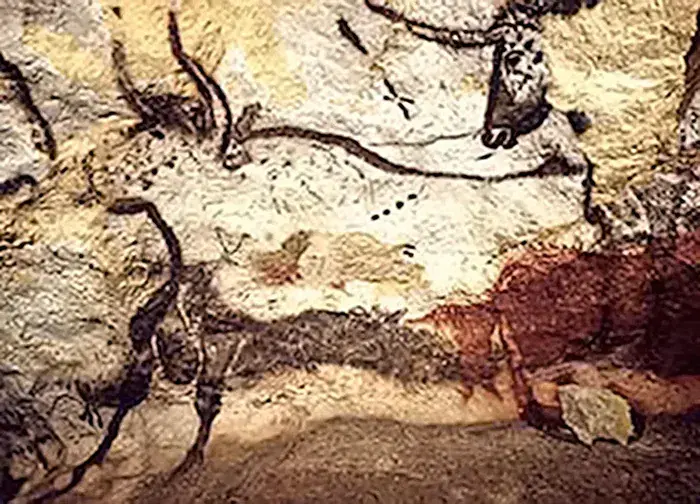

The researchers’ conclusion isn’t final, of course, but separate work has shown that the early modern humans in the region, the Aurignacians, had a whole array of tools to make art and jewelry, which could have been a status symbol. Or maybe they really cared how they looked.