Archaeologists Unearth Prehistoric Village of First Farmers in Israel

It is a rich and fertile land where agriculture is supposed to have started before spreading around the world.

Now archaeologists have discovered a prehistoric village that may have belonged to some of the first farmers on the planet.

Sitting on the east shore of the Sea of Galilee, the 12,000-year-old settlement is believed to have belonged to members of the Natufian culture just as they began shifting from a hunter-gatherer lifestyle to farming.

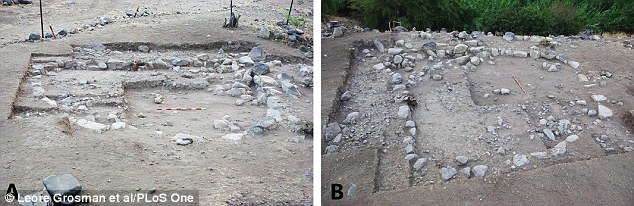

Archaeologists said this was when these first farmers began settling down and building more permanent dwellings from stone. Buried among the remains of up to five different buildings, researchers discovered the remains of at least five people.

They have also discovered huge numbers of stone tools, jewellery and pieces of art carved from stone and bone among the ruins.

The site is providing experts with a unique insight into life at a time when mankind was on the verge of bursting into the Neolithic period and was starting to develop techniques for farming the land.

Dr Leore Grosman, an archaeologist at The Hebrew University of Jerusalem who led the excavation, said the village seemed to be inhabited at this crucial time – showing technology from both the Paleolithic and Neolithic.

Writing in the journal Public Library of Sciences One, she and her colleagues said: ‘The excavation at Nahal Ein-Gev II enables us to closely examine the cultural crossroads at the end of the Paleolithic and the beginning of the Neolithic way of life.

‘Was this extensive and complex occupation a sedentary village?

‘Architectural planning, construction methods and various aspects of the faunal assemblage provide good indications for site permanence.’

The village was unearthed in a wadi, or valley, in the Valley of Jordan in Israel, on the banks of a stream about 1.2 miles (1.9km) from the eastern shore of the Sea of Galilee.

Excavations between 2010 and 2013 revealed the site covered an area of almost 13,000 square ft (1,207 sq metres).

The archaeologists found the remains of several rounded stone buildings, each of which appears to have been dug 15-inches (38cm) into the ground so they were semi-subterranean in nature.

Human remains were unearthed from two locations on the site. One woman had been buried on her back, curled in a tight ball which suggests her body may have been wrapped or placed in a sack.

Four other individuals were found in a larger burial pit – one of which was a female who appears to have been buried in a similar way to the other woman found at the site.

The bones to the other individuals were scattered around her, suggesting the grave had been dug up several times to bury each person, the archaeologists suggest.

Archaeologists also found a rich assembly of stone tools including blades used for butchering and scraping skins, alongside sickle blades that may have been used for cutting crops. Animal remains on the site, however, showed the residents were also still hunting and butchering gazelles. Small numbers of remains from wild cattle, wild goats, wild boar and deer were also found.

Perhaps most intriguingly, however, was the discovery of jewellery and carvings made from stone and bone that suggest the people who lived here had a rich artistic culture.

Two pieces of bone engraved with a delicate motif of repeating geometric triangular patterns and a piece of limestone that appears to have been carved were found during the excavation.

Archaeologists also discovered a rich assembly of jewellery including beads made from Cardium shells and two greenstone pendants or buttons.

The archaeologists said the site appears to have been occupied for several centuries and appeared to have a bustling community that may also have traded with groups from elsewhere.

The greenstone pendants, for example, may have been traded with groups from the Negev in the south or Israel or Hula Valley in the north of modern-day Israel.

Dr Grosman said: ‘Although attributes of the lithic tool kit found at Nahal Ein-Gev II places the site chronologically in the Paleolithic period, other characteristics – such as its artistic tradition, size, the thickness of archaeological deposits and investment in architecture – are more typical of early agricultural communities in the Neolithic period.

‘Characterising this important period of potential overlap in the Jordan Valley is crucial for the understanding of the socioeconomic processes that marked the shift from Paleolithic mobile societies of hunter-gatherers to Neolithic agricultural communities.’