Title: Archaeologists in Zambia discover oldest wooden structure in the world, dating to 476,000 years ago

Researchers have discovered remnants of what is thought to be the world’s oldest known wooden structure, an arrangement of logs on the bank of a river bordering Zambia and Tanzania that predates the rise of modern humans.

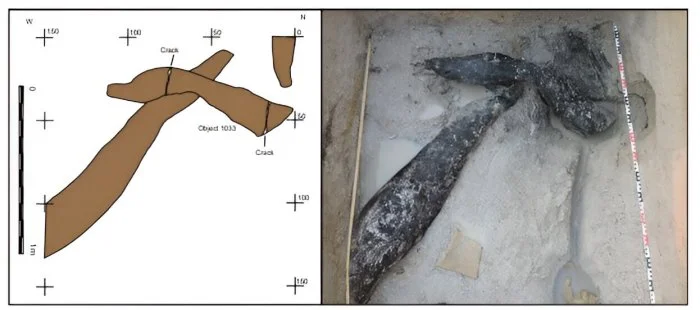

The simple structure, made by shaping two logs with sharp stone tools, may have formed part of a walkway or platform for human ancestors who lived along the Kalambo River nearly 500,000 years ago.

Marks on the logs show they were cut, chopped and scraped with an array of stone tools found at the site. One log, a type of bushwillow, overlies the other and is held in place by a large inverted U-shaped notch in its underside.

“When I first saw it, I thought this can’t be real. The wood and the stone suggest a high level of ingenuity, technological skill and planning,” said Prof Larry Barham, an archaeologist at the University of Liverpool who led the work.

“It could be part of a walkway or part of a foundation for a platform,” he said. “A platform could be used as a place to store things, to keep firewood or food dry, or it might have been a place to sit and make things. You could put a little shelter on top and sleep there.”

Scientists at the University of Aberystwyth dated the structure to at least 476,000 years old, from long before Homo sapiens are thought to have emerged about 300,000 years ago. The structure may be the work of Homo heidelbergensis, a predecessor of modern humans that lived in the region.

The scientists arrived at Kalambo Falls in 2019 hoping to press on with excavations made in 2006, only to find the river had shifted course and flooded the area.

Barham’s plan B involved sliding down a 30ft cliff to a strip of beach on the Kalambo River upstream of a 770ft waterfall that plunges towards Lake Tanganyika. There he found the first of the wooden items recovered on the trip, a digging stick dated to about 390,000 years ago.

Other wooden items included a wedge, a split branch with a notch that may have formed part of a trap, and a log cut at both ends. “It might be a work surface, like a Black and Decker workbench,” Barham said of the log.

The findings, published in Nature, are remarkable because wood so rarely survives for long periods. The material at Kalambo Falls was preserved by waterlogged sediments that are starved of oxygen.

“It may not be the beginning of the built environment, but it is the earliest time we have of people taking trees, taking charge of this material, and shaping something that has no precedent, that has no natural form to emulate,” Barham said. “It’s a real cultural imposition on the landscape.”

The site probably contains more ancient wooden objects, and Barham said the priority was to work with the Zambian government to get Kalambo Falls recognised as a Unesco world heritage site.

Dr Sonia Harmand, an expert in early Stone Age archaeology at Stony Brook University in New York called it a groundbreaking discovery.

“We know so few things about the use of organic materials during the early stages of our evolution that this makes it a very wanted discovery,” she said. “The team is formed of world experts and no doubt the discovery is solid.”

Dr Annemieke Milks, a Palaeolithic archaeologist at the University of Reading, said the interlocking, shaped logs were evidence of a “behavioural threshold”, showing that as early as 476,000 years ago, humans used large-scale materials to transform their lived environment.

“Although quite simple in nature, the shaped and interlocking logs indicate that these humans structured their environment,” she said. “While many other animals engage in such behaviours, the Kalambo Falls humans made use of multiple materials – at the very least stone and wood, and possibly fire – to do so.

“The rarity of wood preservation implies that such behaviours were more widespread than what we witness in the archaeological record,” she added.

“Although the use of wood for tools and structures remains commonplace today, their findings provide a rare glimpse into the role that this simple material played in human evolution.”