Cave on Borneo: 20,000 Years of History and Colonial Resistance Revealed through Rock Art

The islands of South-East Asia record a long and dynamic human history of technological innovation, migration and conflict.

The region’s rock art stretches back more than 45,000 years. It’s a unique source of information about this complex human past.

But rock art doesn’t just record ancient history. Researchers have identified artwork documenting the more recent past, including Indigenous resistance to colonial occupation, violent frontier conflicts and enslavement.

Our new study shines a new light on rock art of Sarawak (a state of Malaysia on the island of Borneo). The rock art we have dated records resistance to colonial forces in Malaysian Borneo during the 17th to 19th centuries.

Rock art in Borneo

Black drawings of people, animals, ships and abstract geometric designs dominate caves throughout Borneo’s north-west.

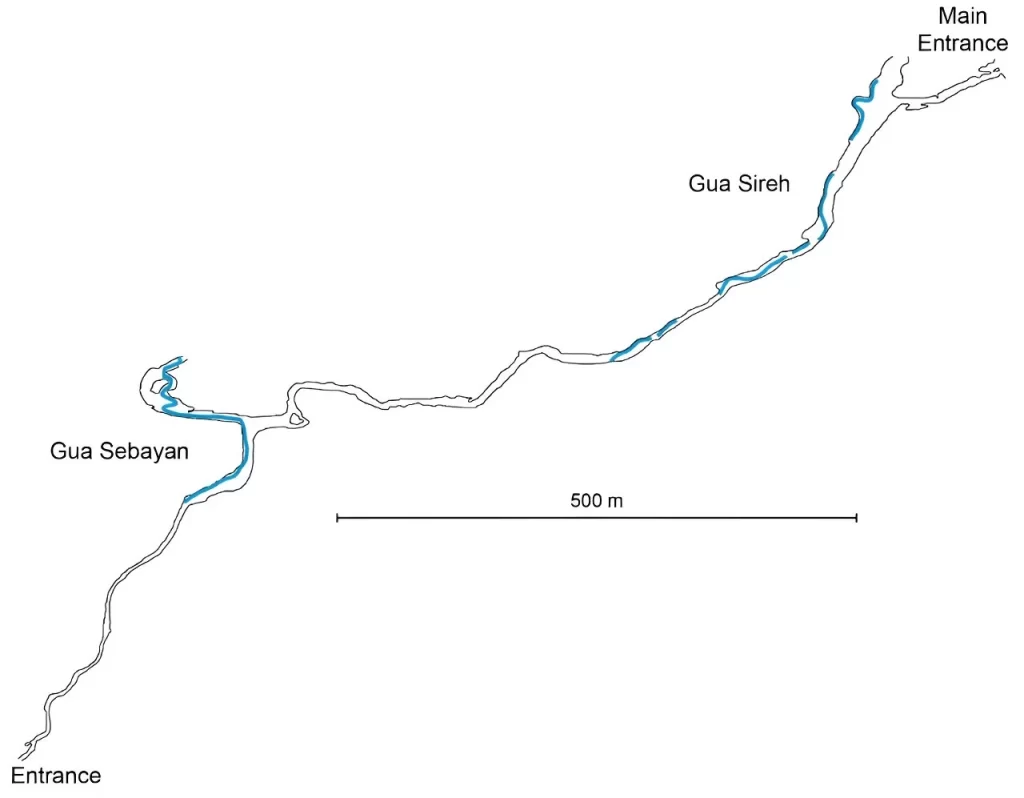

Gua Sireh is one of the region’s best-known rock art sites, attracting hundreds of visitors each year. The cave is about 55 kilometers south-east of Sarawak’s capital, Kuching.

Hundreds of charcoal drawings cover the walls of Gua Sireh. People are shown wearing headdresses. Some are armed with shields, knives and spears in scenes of hunting, butchering, fishing, fighting and dancing.

Excavations in the 1950s, 1970s and 1980s revealed people intermittently used Gua Sireh for around 20,000 years, before abandoning the site around 1900.

The Indigenous people who used the cave were the ancestors of the contemporary Bidayuh (inland tribal people), also known as “Land Dayaks” in early ethnographic accounts.

Malayo-Polynesian Austronesian speakers (whose language originates in Taiwan) spread across Island South-East Asia and the Pacific starting around 3,000 to 4,000 years ago.

Austronesian influence at Gua Sireh dates from about 4,000 years ago, indicated by the first appearance of charred rice and pottery.

The presence of Austronesian communities at Gua Sireh is a part of broader evidence for dynamic human migrations in the region over thousands of years.

Further cultural interactions at the site occurred around 2,000 years ago, with grave goods, such as glass beads, showing contact between the Bidayuh and coastal traders.

In the 17th to 19th centuries, there was a period of increasing conflict when Malay elites controlling the region exacted heavy tolls on local Indigenous tribes. Using radiocarbon dating, we have been able to date two large, elaborate human figures to this period. They were drawn between 1670 and 1830.

We interpreted our results informed by the oral histories of the Bidayuh, who have continuing custodial responsibilities over the site today.

Our findings sit alongside other recent archaeological work that has highlighted Indigenous resistance to colonial occupation.

Carbon dating the images

In addition to radiocarbon dating and oral history, another strand of evidence we used to interpret these new dates were the images themselves.

One figure we looked at in our carbon dating brandishes two short-bladed Parang Ilang, the principal weapon used during the warfare that marked the first decades of white rule in Borneo. We have dated this figure as drawn between 1670 and 1710 when Malay elites dominated the Bidayuh.

In another image we studied, large human figures are shown holding distinctive weapons such as a Pandat—the war sword of Land Dayaks, including the Bidayuh. Pandat were used exclusively for fighting and protection, never in agriculture or handicrafts, suggesting the drawing relates to conflict.

We have dated this figure to between 1790 and 1830. This was a period of increasing conflict between the Bidayuh and Iban (Indigenous peoples from the coast, also known as Sea Dayaks) and Brunei Malay rulers.

During this period many Indigenous Sarawakians moved into the upland interior, including the Gua Sireh area, to escape persecution.

Brunei rulers were known to not only bully and enslave people but also allowed expeditions of Ibans to attack the Bidayuh. The Ibans were said to keep the heads of the people they slaughtered and handed over the “slaves” they captured to the Brunei authority.

An example from Bidayuh oral histories of the cave being used as a refuge during territorial violence comes from 1855.

The British diplomat Spenser St John was shown a skeleton in Gua Sireh. A local tribesman said he had shot this man years earlier, before the rule of James Brooke, which began in 1839.

The shooting resulted from a skirmish with a very harsh Malay chief who had demanded the Bidayuh hand over their children. They refused and retreated to Gua Sireh where they held off a force of 300 armed men.

Suffering some losses (two Bidayuh were shot, and seven were taken prisoner and enslaved), most of the tribe escaped through the far side of the cave complex, saving their children.

Oral histories combined with the figures holding weapons of warfare contextualize the ages we now have for the rock art.

The direct dates we have produced demonstrate distinct periods of drawing can be identified.

The ubiquity of black drawings across the region and their probable links to the migrations of Austronesian and Malay peoples opens exciting possibilities for further understanding the complexities of rock art production in Island South-East Asia.