Unlocking Human Ancestry: Surprising Insights from the Broken Hill Skull and Homo Heidelbergensis

The evolution of our species is a fascinating and complicated subject. Scientists often discuss our long-gone relatives, the Neanderthals, and some studies attempt to unravel the truth about the intriguing Denisovans.

There are also other ground-breaking discoveries that can shed more light on the evolution of humans.

One such finding occurred in 1908 when fossils of an archaic human were discovered by a workman in the Rösch sandpit just north of the village of Mauer, near Heidelberg, Germany.

Scientist Otto Schoentensack, who was the first one to examine and describe the fossil came up with the name Homo heidelbergensis. 1

Who Was Homo Heidelbergensis?

Today, the fossil of Homo heidelbergensis is recognized as one of the classical finds of paleoanthropology. Homo heidelbergensis lived in Europe, possibly Asia (China); Africa (eastern and southern).

Scientists have long suggested Homo heidelbergensis who knew how to control fire by building hearths or early fireplaces and use of wooden spears, lived about 700,000 to 200,000 years ago.

“Why did they come together at these early hearths? Perhaps to socialize, to find comfort and warmth, to share food and information, and to find safety from predators.

H. heidelbergensis probably took advantage of natural shelters but this species was also the first to build simple shelters.” 2

Other archaeological discoveries suggest Homo heidelbergensis engaged in rituals, and these ancient humans were capable of producing tools such a for example a handaxe.

According to the Smithsonian’s National Museum of Natural History, “this species may reach back to 1.3 million years ago, and include early humans from Spain (‘Homo antecessor’ fossils and archeological evidence from 800,000 to 1.3 million years old), England (archeological remains back to about 1 million years old), and Italy (from the site of Ceprano, possibly as old as 1 million years).

Comparison of Neanderthal and modern human DNA suggests that the two lineages diverged from a common ancestor, most likely Homo heidelbergensis, sometime between 350,000 and 400,000 years ago – with the European branch leading to H. neanderthalensis and the African branch (sometimes called Homo rhodesiensis) to H. sapiens.”

There is no doubt that Homo heidelbergensis played an important part in the history of human evolution. Still, the discovery of an ancient skull provided scientists with intriguing questions leading to new theories about the species.

Riddle Of The Broken Hill Skull

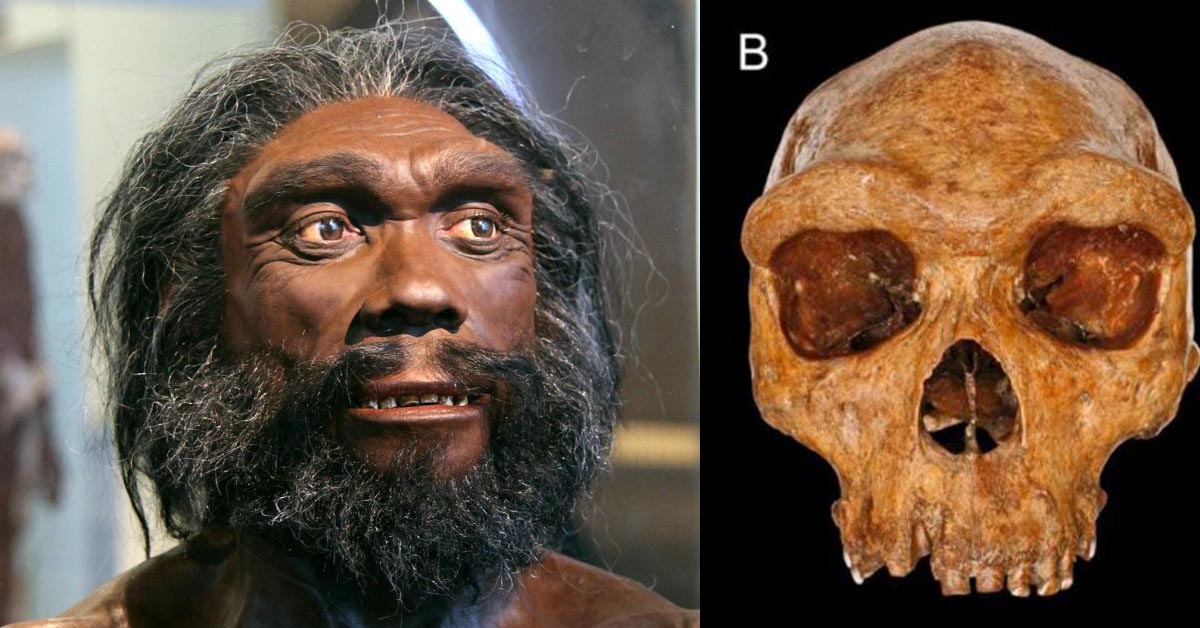

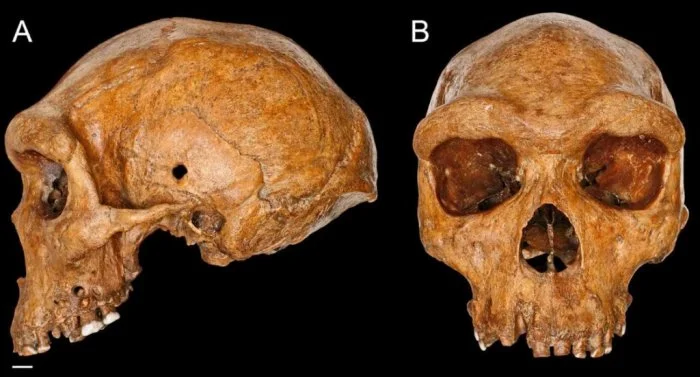

Discovered in 1921 by miners in what is now Kabwe, Zambia, the Broken Hill (Kabwe 1) skull is one of the best-preserved fossils of the early human species Homo heidelbergensis and was estimated to be about 500,000 years old.

At the time of the discovery, the Broken Hill remains were difficult to date due to their haphazard recovery and the site being completely destroyed by quarrying.

Some years ago, Professor Rainer Grün from the Environmental Futures Research Institute led the team which analyzed the skull and other fossil human remains found in the vicinity, including a tibia and femur midshaft fragment. The results of the study led to a ground-breaking discovery.

Using radiometric dating methods, Professor Grün and his colleagues estimated the Broken Hill skull is between 274,000 and 324,000 years old. It is much younger than previously thought.

So, why is the dating of such importance, some will ask?

According to Professor Grün “the new best age estimate of the fossil impacts our understanding of the tempo and mode of modern human origins.”

The research also suggests that human evolution in Africa around 300,000 years ago was a much more complex process, with the co-existence of different human lineages.

“Previously, the Broken Hill skull was viewed as part of a gradual and widespread evolutionary sequence in Africa from archaic humans to modern humans. But now it looks like the primitive species Homo naledi survived in southern Africa, H. heidelbergensis was in Central Africa, and early forms of our species existed in regions like Morocco and Ethiopia,” Professor Grün said.

Professor Grün said his team’s research adds to new and emerging studies which question the mode of modern human evolution in Africa and whether Homo heidelbergensis is a direct ancestor of our species.

Professor Chris Stringer, a researcher in human evolution at the Natural History Museum, has worked with geochronologist Rainer Grün and other colleagues to produce the best estimate for when the owner of the Broken Hill skull died said the Broken Hill skull is surprisingly young.

“We already knew that Eurasia contained diverse human lineages about 300,000 years ago. Now, the same applies to Africa, since H. heidelbergensis must have been contemporary with more sapiens-like fossils in Morocco and Kenya and the much more primitive Homo naledi, recently discovered in South Africa.

“It is now looking like Africa and Eurasia were inhabited by a whole range of hominin species just a few hundred thousand years ago. While H. naledi was living in South Africa, H. heidelbergensis was surviving in South-Central Africa, and H. sapiens was emerging in Morocco and Ethiopia.

At the same time as all this H. neanderthalensis was evolving in Europe, the Denisovans were developing in Asia, Homo erectus may still have been clinging on in Indonesia, and two diminutive hominins, Homo floresiensis and Homo luzonensis, were living the island life in Southeast Asia.

It seems that the world was a busy place, and we’re only now starting to understand what this may mean for our own origins.” 4