Neanderthals were not driven to extinction by lack of intelligence, but interbreeding, study shows

They are often depicted as dim-witted evolutionary losers, but Neanderthals were not driven to extinction by their lack of brains, a new study suggests.

Instead, it is more likely that they disappeared 40,000 years ago because of interbreeding and assimilation with our early modern human ancestors, scientists believe.

An analysis of archaeological evidence dating back 200,000 years strips away some of the myths surrounding Neanderthals and reveals they were more advanced and sophisticated than has widely been thought.

The differences between the two human sub-species are not enough on their own to account for the demise of the Neanderthals, say the two US and Dutch researchers.

Dr Paola Villa, from the University of Colorado Museum, and Professor Wil Roebroeks, from Leiden University, wrote in the online journal Public Library of Science ONE: ‘Genetic studies now suggest that the debate on the demise of the Neanderthals needs to be reframed in terms of some degree of interbreeding.

‘In that sense, Neanderthals did not go extinct, even though their distinctive morphology did disappear.

‘We conclude that all the “archaeology-based” explanations for the demise of the Neanderthals… are flawed.’

Neanderthals thrived in Eurasia for 300,000 years but vanished around 40,000 years ago as early modern humans began to settle in Europe.

In the past, experts have theorised that Neanderthals died out because they were mentally, technologically and culturally inferior to the newcomers and unable to compete for limited resources.

But more recent evidence has shown that Neanderthals made effective tools and weapons, wore ornaments such as eagle claws, used ochre and pitch, ate plants and fish as well as big game and created organised living spaces in their caves.

In many cases this was happening before the arrival of modern humans, so the behaviours could not have been copied from them.

Reviewing the evidence, the scientists pointed out that 200,000 years ago Neanderthals were using fire to produce pitch from tree bark.

Experiments showed that the process required high temperatures and an oxygen-free environment such as an enclosed pot, suggesting a high level of technical knowledge.

Neanderthal DNA, which was sequenced in 2010, shows clear evidence of interbreeding, the researchers add. Neanderthals and early modern humans are most likely to have interbred in Europe and the Middle East around 50,000 years ago.

Today Neanderthal inheritance is estimated to make up between 1% and 4% of the DNA of people outside Africa.

Interbreeding could be one reason why Neanderthals vanished, according to the scientists. They were not so much driven to extinction as assimilated.

Evidence of the two mixing can be seen in the fossil record. Some human-like characteristics have been found in late Neanderthal fossils, and conversely, Neanderthal features have been seen in early specimens of modern humans in Europe.

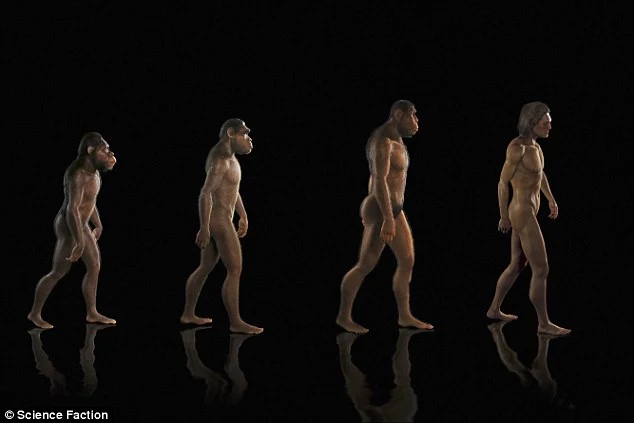

Neanderthals were more robust and much stronger than modern humans, with a backward sloping chin and forehead.

It is possible that interbreeding with Neanderthals may have helped our ancestors survive outside Africa, say the scientists. On the other hand some Neanderthal genes may have contributed to sterility, which is why so few remain.

The researchers wrote: ‘The Neanderthal demise appears to have resulted from a complex and protracted process including multiple dynamic factors such as low population density, interbreeding with some cultural contact, possible male hybrid sterility and contraction in geographic distribution followed by genetic swamping and assimilation by the increasing numbers of modern immigrants.’

EUROPEANS MORE CLOSELY RELATED TO NEANDERTHALS THAN AFRICANS

Europeans may be closer to their Neanderthal cousins than previously thought, new research suggests.

Breeding with Neanderthals has long been known to have left its traces in the DNA of modern Europeans.

Scientists in Edinburgh have now confirmed that the genetic similarity between the two must have arisen after interbreeding in Europe and Asia, before our ancestors spread across the globe.

Previous research speculated that modern Europeans and Asians are related to Neanderthals because they originated from a similar sub-population in Africa.

Both groups evolved from a common ancestor in Africa before spreading to other parts of the world.

The two groups emerged at different times with Neanderthals leaving the African continent more than 200,000 years before humans did.

Now scientists at the University of Edinburgh and Wageningen University found the species mated in Europe and Asia thousands of years ago.

The research involved dividing up the genetic code of each sub-species to calculate the statistical likelihood of distant or recent interbreeding.

They traced the biological ties that exist between humans and the ancient species which are believed to have died out around 30,000 years ago.

The research found that the two per cent of neanderthal DNA which exists in people today came from the mating outside of Africa.