Oldest Known Spearthrowers Found At 31,000-Year-Old Archaeological Site Of Maisières-Canal

Archaeologists in Belgium have demonstrated that spearthrowers were used for launching projectiles armed with tanged flint points at the Early Upper Paleolithic site of Maisières-Canal around 31,000 years ago.

Humans have been hunter-gatherers for most of our past, but scientists still lack knowledge about what our prehistoric ancestors gathered and how they hunted because of the near lack of organic preservation at Paleolithic sites.

Of these two modes of subsistence, hunting tends to be better visible archaeologically because it can leave behind durable stone and bone implements that once served as weapon components.

Four weapon systems — thrusted spears, thrown spears, the spearthrower, and the bow — are assumed to have existed in the Stone Age, but the timing of their invention and their possible co-existence remain debated.

“Until now, the early weapons have been infamously hard to detect at archaeological sites because they were made of organic components that preserve rarely,” said lead author Dr. Justin Coppe, a researcher in TraceoLab at the University of Liège.

“Stone points that armed ancient projectiles and that are much more frequently encountered at archaeological excavations have been difficult to connect to particular weapons reliably.”

“Most recently published claims for early use of spearthrowers and bows in Europe and Africa have relied exclusively on projectile point size to link them to these weapon systems.”

“However, ethnographic reviews and experimental testing have cast serious doubt on this line of reasoning by showing that arrow, dart, and spear tips can be highly variable in size, with overlapping ranges.”

In the research, Dr. Coppe and colleagues examined a sample of 329 flint artifacts from the site of Maisières-Canal, which is located in Belgium near the town of Mons, on the northern edge of the alluvial plain of the Haine.

“Maisières-Canal is a reference site for the Early Upper Paleolithic of north-west Europe and one of the few Early Upper Paleolithic open-air sites known from the region,” the researchers said.

“The site has been interpreted as having a single main Early Upper Paleolithic occupation layer that shows limited vertical displacement of finds.”

“Thirteen radiocarbon dates consistently place the occupation to around 28,000-31,000 years ago.”

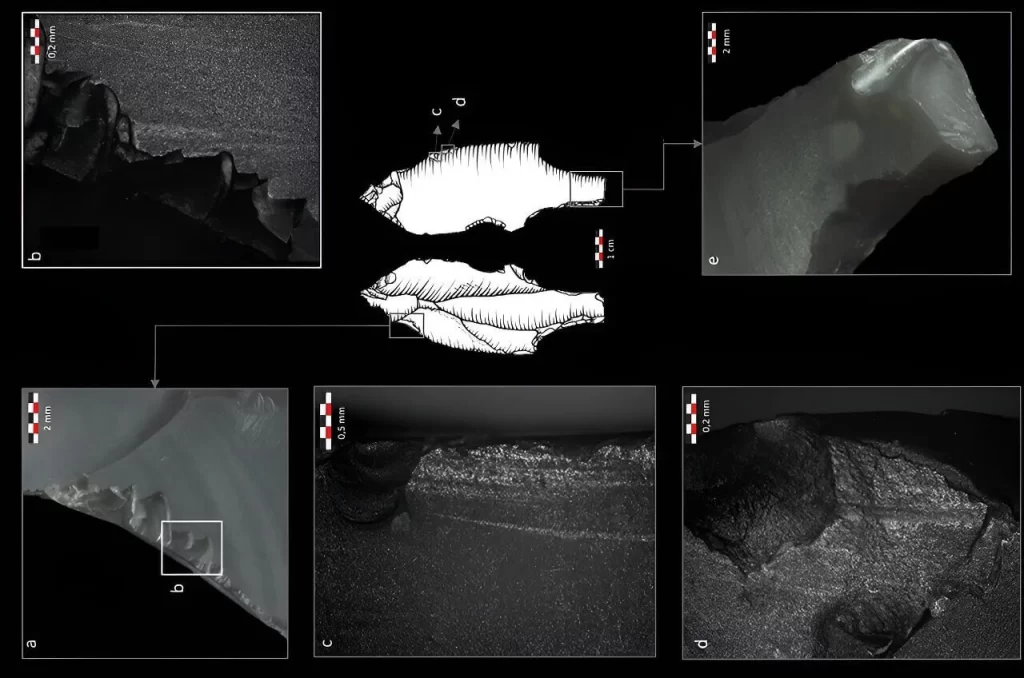

The excellent preservation of the stone points, their large number, their distinct morphologies, and recent technological analyses that allowed their careful experimental replication presented a unique opportunity to reconstruct the delivery systems with which the projectiles were shot.

“We carried out a large-scale experiment in which we fired replicas of Paleolithic projectiles using different weapons such as spears, bows and spearthrowers,” said Dr. Noora Taipale, also from TraceoLab at the University of Liège.

“By carefully examining the fractures on these stone points, we were able to understand how each weapon affected the fracturing of the points when they impacted the target.”

“Each weapon left distinct marks on the stone points, enabling us to match these marks to archaeological finds.”

“In a way, it’s like identifying a gun from the marks the barrel leaves on a bullet, a practice known from forensic science.”

“The excellent match between the experimental spearthrower sample and the Maisières-Canal projectiles confirmed that the hunters occupying the site used these weapons.”

The findings push back the dates for spearthrower use in Europe by over 10,000 years.

“Representing the first attempt to carefully consider the idiosyncrasies of different prehistoric weapons in all their complexity, our results provide the thus far oldest reliable evidence for the use of long-range weaponry in prehistoric hunting,” the scientists said.

The study was published in the journal Scientific Reports.