Remains of two men from central China shed light on ancient practice of punitive amputation

The discovery of two ancient skeletons exhibiting remarkably similar injuries is an intriguing archaeological find.

These unrelated individuals, who lived over 2,000 years ago, both had approximately one-fifth of their lower leg bones missing, with the precise length of bone loss matching down to the centimeter.

This peculiar coincidence has piqued the interest of researchers, as it presents a puzzling mystery reminiscent of a crime scene investigation.

Dr. Qian Wang, a paleoanthropologist and professor at Texas A&M University’s School of Dentistry, has undertaken the task of examining these remains. His expertise in ancient Chinese cultures and burial practices has enabled him to unravel crucial details about the identities of these individuals and the potential causes behind their matching limb losses.

Through meticulous analysis, Dr. Wang’s research aims to shed light on the lives and circumstances surrounding these two enigmatic figures from the past.

Wang’s study reveals that both men were members of the aristocracy during the Eastern Zhou Dynasty. Notably, they were likely subjected to an ancient form of criminal punishment called Yue.

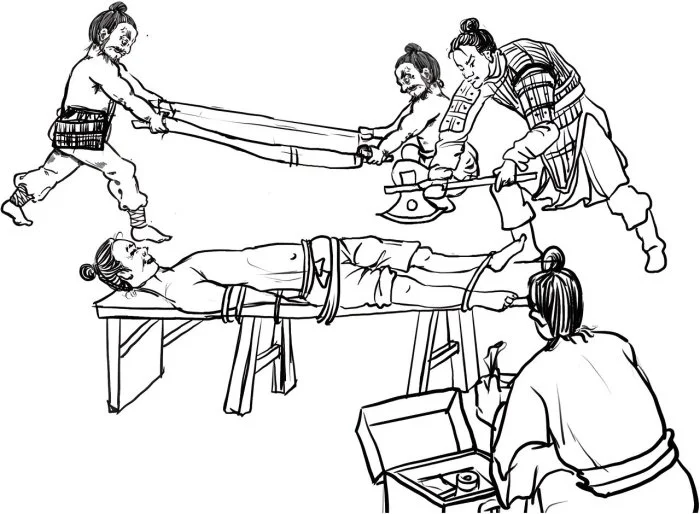

This practice aimed to permanently shame and impair criminals by removing parts of their bodies. The study provides insights into the harsh punitive measures employed in that era, shedding light on the societal norms and judicial systems of the time.

“Based on penal laws of the Zhou Dynasty, Yue, or punitive amputation, was executed in criminal cases including deceiving the monarch, fleeing from duties, stealing, and so on,” Wang explained, noting that this form of punishment was one step below execution in the Zhou penal system. “On some occasions, it could (serve as) a reduced penalty in lieu of death to reflect leniency.”

“Based on penal laws of the Zhou Dynasty, Yue, or punitive amputation, was executed in criminal cases including deceiving the monarch, fleeing from duties, stealing, and so on,” Wang explained, noting that this form of punishment was one step below execution in the Zhou penal system. “On some occasions, it could (serve as) a reduced penalty in lieu of death to reflect leniency.”

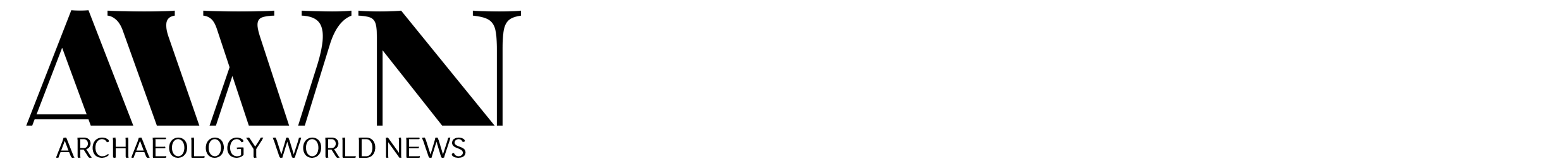

In this particular case, the remains of two men from the Zhou Dynasty period, dating back 2,300 to 2,500 years ago, were discovered at an archaeological site in Sanmenxia City, located along the Yellow River about 500 miles southwest of Beijing. The skeletal analysis revealed that both individuals had undergone punitive amputation, with one of their feet and approximately 8 centimeters or one-fifth of a leg removed.

According to Wang, this type of amputation was consistent with the Zhou Dynasty’s punitive practices, mirroring the remains of other individuals believed to have been similarly punished during that period. While amputations were also performed for medical purposes to treat trauma and disease, Wang stated that, in this case, penal amputation is the most plausible explanation based on the historical and archaeological context.

The skeletons of these two men, who died at different times during the specified period, were unearthed at the archaeological site in the northwestern part of Sanmenxia City. Although it is impossible to determine the exact nature of their offenses, Wang suggested that the severity of their crimes may have differed, as historical evidence indicates that amputation of the right leg was reserved for more serious offenses.

“Punitive amputation of both feet was reserved for even higher serious felonies.

Since amputation by penalty was not an uncommon phenomenon, they might (have) returned to normal social life and were buried in a proper manner after death,” Wang said, noting that the men’s high status likely eased their physical and social recovery.

These cases enrich our understanding of the penal laws and their implementations, medical care capabilities, and the general benevolent attitudes towards those who were punished by law from the social and archaeological contexts of ancient China,” Wang said.

As part of their investigation, Wang and his fellow researchers utilized existing knowledge of Zhou-era burial practices to determine the position of the two men within the social and political hierarchy. The Zhou Dynasty had a distinct hierarchical system called The Way of Rituals, which defined the different social statuses of people during life and after death. This system was mapped into burial patterns, whereby social status was indicated by tomb sizes, tomb orientations, layers of coffin, and grave goods.

The existence of multi-layered coffins for higher-ranking individuals is particularly useful, as the number of layers can be analyzed to narrow down their position within this hierarchy. Seven coffin layers were used for a king, five for regional rulers, three for high-level government officials, and two for low-level officials.

In this research, two individuals were buried in two-layered coffins in a north-south direction, typically reserved for upper-class members, with commoners relegated to smaller, east-west-oriented tombs.

The presence of goods such as pots and stone tablets at the graves further strengthens the case for the men being social elites. Additionally, an analysis of specific isotopes in the subjects’ bone tissue implied that they were both well-nourished, another clue pointing to their elevated status.

In many ancient societies, the reduction or removal of body parts was a common form of punishment for crimes such as theft, vagrancy, and false witness, according to Wang. In addition to leg amputations, other forms of bodily punishment practiced in Zhou Dynasty China involved removing the convicted person’s nose or genitals. These severe punishments were implemented as a means of enforcing societal norms and deterring criminal behavior in those times.

“Punitive amputation was officially stopped in the Han Dynasty during the reign of Wendi in 167 BCE, with a decree to stop ‘punishment by body reduction,'” Wang said. “It was replaced with more humane measures such as flogging, hard labor and/or imprisonment.

“However,” he said, “the practice was not totally eradicated. Evidence of punitive amputations, most commonly of the foot, were still found in subsequent dynasties; the latest case was from the Qing Dynasty (1644–1911 CE), in which both feet of a male individual were amputated by sawing.”

Punitive amputations were a harsh reality during the Zhou Dynasty, and some notable victims have become iconic figures in Chinese history and lore. The military strategist and writer Sun Bin, as well as Bian He, suffered this cruel fate.

Bian He’s unfortunate tale is particularly poignant. According to historical accounts, he presented a valuable jade to the kings of the Chu State, but they doubted its authenticity.

As punishment for perceived deception, they amputated first his left foot and then his right, only to later discover that the jade was indeed genuine.

Such punitive amputations of feet and legs were so commonplace that the legendary philosopher Han Feizi made special note of it in his writings.

This practice even spawned a famous Chinese idiom, suggesting that due to the prevalence of this cruel punishment, shoes became cheaper while prosthetics became more expensive.

These accounts shed light on the harsh realities of the time and serve as a reminder of the inhumane practices that once existed.

The study was published in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences