Researchers Successfully Extract Ancient DNA From 2,900-Year-Old Clay Brick

For the first time, researchers have been able to extract DNA fragments from an ancient clay brick, demonstrating how these building blocks from times long past could be used to catalog flora found in the environment at the time.

When this brick was made some 2,900 years ago in what is now northern Iraq, the process would have involved mixing mud from the banks of the Tigris river, with materials such as chaff, straw, or animal dung.

Small plant particles amid the animal waste and straw can remain protected inside the brick for millennia – as has now been demonstrated by the team from the University of Oxford in the UK and the National Museum of Denmark and the University of Copenhagen in Denmark.

Having extracted a sample of the brick, the researchers used an analytical technique previously used on other forms of porous material, such as bone.

This gave them the ability to sequence (or decode) the DNA in the plant matter, identifying 34 distinct taxonomic groups of plants.

“We were absolutely thrilled to discover that ancient DNA, effectively protected from contamination inside a mass of clay, can successfully be extracted from a 2,900-year-old brick,” says biologist Sophie Lund Rasmussen from the University of Oxford.

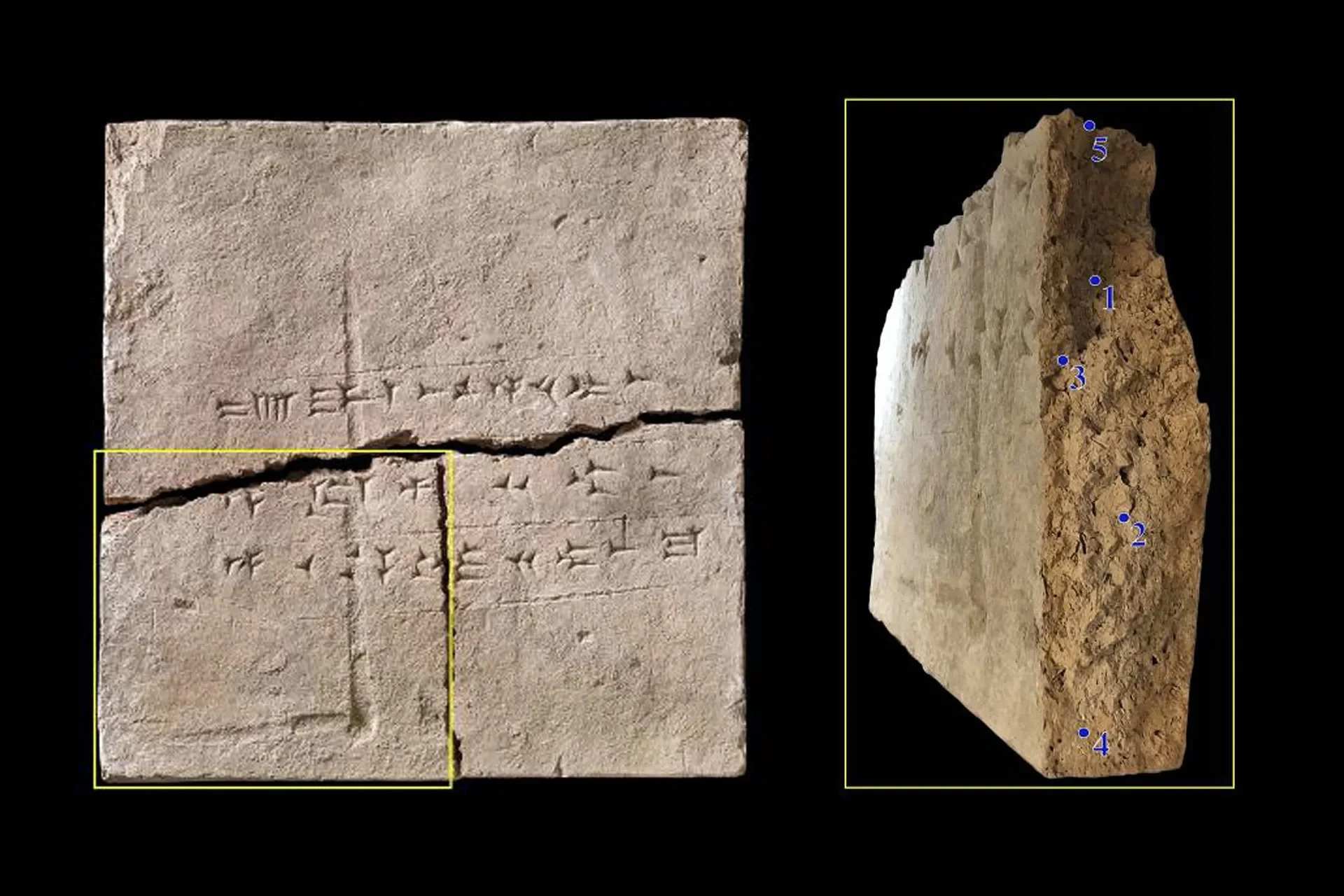

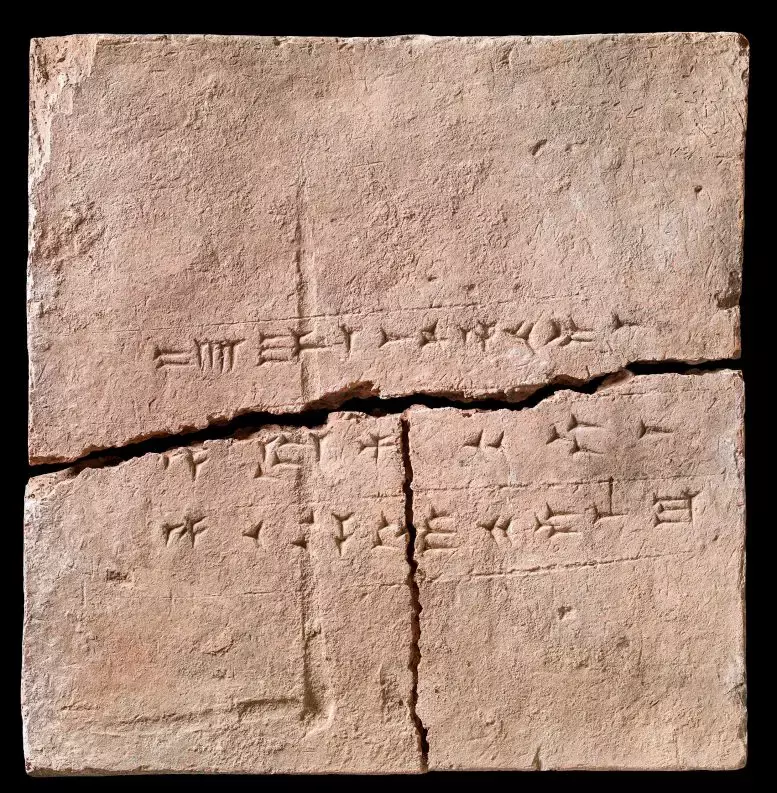

The brick analyzed in this study was found in the palace of the Neo-Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II, located in the ancient city of Kalhu.

Dating it to some time between 879 and 869 BCE – the years the palace was under construction – was made easier by an inscription in the clay that specifically mentioned the palace.

Plant families with the most abundant DNA in the brick included Brassicaceae (the cabbage and mustard family) and Ericaceae (heather), while genetic material from Betulaceae (birch), Lauraceae (laurels), Selineae (the family containing carrots and parsley), and Triticeae (cultivated grasses) was also present.

“The brick serves as a biodiversity time capsule of information regarding a single site and its surroundings,” says Assyriologist Troels Arbøll, from the University of Copenhagen.

“In this case, it provides researchers with a unique access to the ancient Assyrians.”

The team concentrated on plant DNA because it was the most well-preserved, but the same techniques could be used to look for animal DNA too.

Clay bricks are found in a host of archaeological sites across the world, and have the potential to reveal all kinds of new information about the ecosystems and environments they were made in.

In this case, the fact the clay brick had been left to dry naturally rather than fired helped preserve its organic contents, as did the taking of the sample from the middle of the brick where the material was well protected.

Ultimately its an invaluable insight into ancient civilizations, and how our world has changed over thousands of years.

“This research project is a perfect example of the importance of interdisciplinary collaboration in science, as the diverse expertise included in this study provided a holistic approach to the investigation of this material and the results it yielded,” says Rasmussen.

The research has been published in Scientific Reports.