Some of the first humans in the Americas came from China, study finds

Ice age groups in the ancient northern coast of China helped make up the first wave of people to settle the New World, a new DNA study suggests.

The ancient groups may have also migrated to Japan, potentially helping explain similarities in Stone Age artifacts in the Americas, China and Japan, according to the study, published Tuesday (May 9) in the journal Cell Reports.

There are two leading models as to how people first migrated to the Americas. The older idea suggests that ancient Siberians made this journey when the Bering Land Bridge — the landmass that once connected Asia with North America — was relatively free of ice.

More recent evidence argues that multiple waves of humans journeyed to the Americas from various parts of Eurasia, perhaps on watercraft along the Pacific coasts of Asia, the Bering Land Bridge and North America.

To shed light on the origins of Indigenous Americans, scientists examined DNA from mitochondria, the powerhouses of the cell. Mitochondria possess their own genes, which are passed down from the mother.

The researchers analyzed more than 100,000 contemporary and 15,000 ancient DNA samples from across Eurasia. They focused on a rare mitochondrial DNA lineage called D4h, which is currently found in only about 1 in 200 people worldwide.

“This genetic type had only been sporadically reported in different studies,” study lead author Yu-Chun Li, a molecular anthropologist at the Kunming Institute of Zoology in China, told Live Science in an email.

“Therefore, this female lineage, as well as its origin and dispersal history — especially its dispersal into the Americas — gained little attention until now.”

Previous research found that one branch of D4h, known as D4h3a, was seen in Indigenous Americans, while another offshoot named D4h3b was detected in China and Thailand. This suggested that ancient members of the D4h lineage might help bridge Asia and the Americas.

“The most difficult work was to collect as many samples belonging to D4h as we could,” study senior author Qing-Peng Kong, an evolutionary geneticist at the Kunming Institute of Zoology, told Live Science in an email.

By comparing mutations seen in mitochondrial DNA over time, as well as the geographic locations and radiocarbon dates of the fossils from which ancient DNA was collected, the scientists found D4h3a likely originated in northern coastal China.

“The ancestral sources of Native Americans in Asia are more complicated than previously indicated,” Li said.

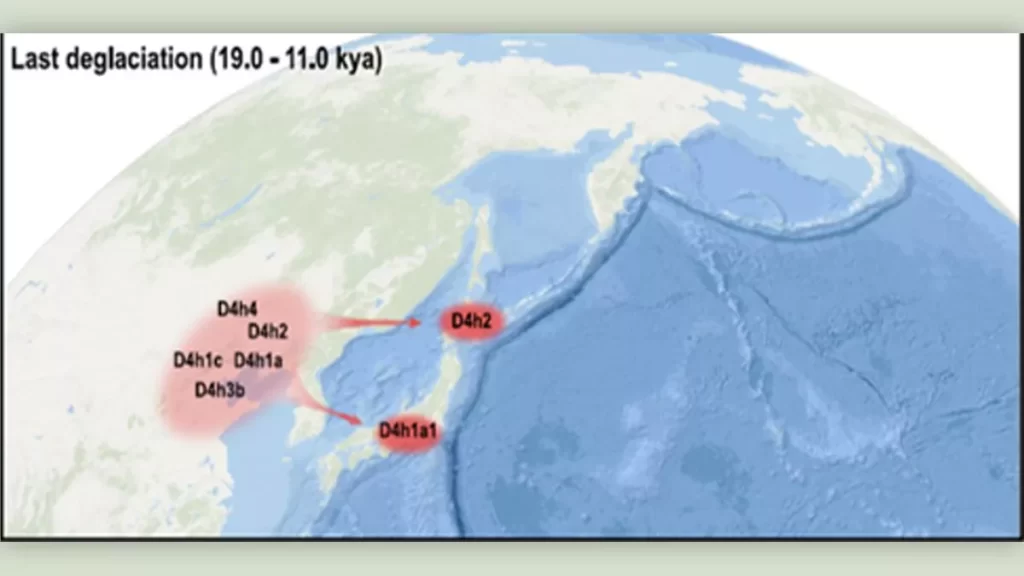

The new findings suggest that the ancestors and closest relatives of D4h3a entered the Americas through at least two migrations.

Both diasporas apparently occurred when the land bridge from Asia to the Americas was obstructed by ice, so the researchers suggest that ice age people may have traveled via the Pacific coast instead.

The first migration likely happened between 19,500 and 26,000 years ago, during the Last Glacial Maximum, the coldest part of the last ice age, the researchers said. Back then, ice sheets covered much of the planet, and living in northern China would have likely proven difficult for humans.

The scientists estimated the second event apparently occurred between 19,000 and 11,500 years ago, when the ice sheets began melting.

Prior work suggested this climate shift likely helped support the rapid growth seen in human populations during this era, which may have helped drive their spread into other regions.

Surprisingly, the researchers discovered that during the second wave, one lineage branched out from northern coastal China and traveled to Japan, where they contributed to the Japanese gene pool, especially the indigenous Ainu people. “This points to an unexpected genetic link between Native Americans and the Japanese,” Kong said.

In all, the new study “matches well with what we know about the archaeological record of Japan, and lends weight to current models of how humans came to populate the Americas,” Loren Davis, an archaeologist at Oregon State University in Corvallis who did not take part in this research, told Live Science in an email.

This discovery may help explain some archeological similarities that prior work controversially suggested at times existed between Stone Age peoples in China, Japan and the Americas.

Specifically, researchers had argued the three regions possessed similarities in how they crafted “stemmed projectile points” for arrowheads and spears.

Although the scientists focused on mitochondrial DNA, additional genetic analyses they conducted suggest that male ancestors of Indigenous Americans also lived in northern China at about the same time as these female ancestors.

However, while the new study is exciting, it’s just “another piece of the puzzle,” on how and when ice age humans first populated the Americas, Davis said.

For instance, the researchers stressed that while these new findings suggest this single northern Chinese lineage may have contributed to Indigenous American ancestry, “it does not represent the whole history of all Native Americans,” Li said. “Investigating other lineages showing genetic connections between Asia and the Americas will help obtain the whole picture of the history of Native Americans.”