Southern Spain’s Nerja Cave Reveals Over 40,000 Years of Continuous Human Visits and Palaeolithic Art

A cave in southern Spain has been continuously visited by humans for over 40,000 years, new research has revealed.

After analyzing charcoal and soot left by the torches that have lit the cavern since time immemorial, the study authors confirmed that the spot saw more prehistoric incursions than any cave other in Europe.

Located in the province of Malaga, the Nerja Cave is famous for the paleolithic art that has been left on its walls by various generations of prehistoric inhabitants.

Ranging from simple dots and lines to more complex zoomorphic designs, the drawings reflect the cognitive, cultural, and technological capacities of the different humans to have entered the cave, and point to a long history of use spanning thousands of years.

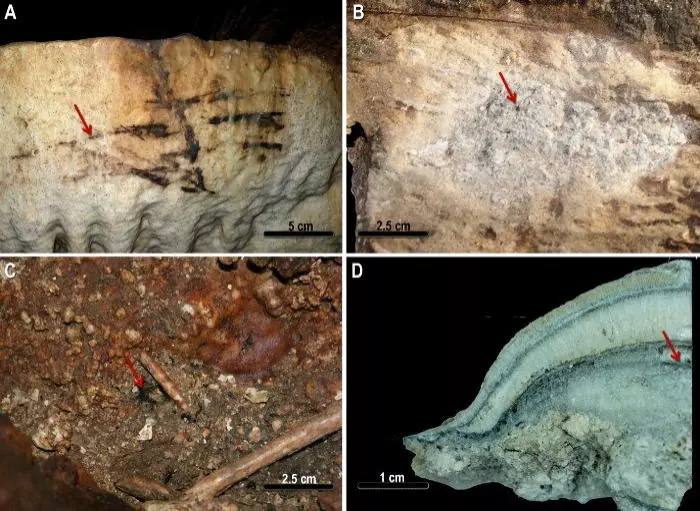

Being pitch black inside, the cave would have been lit by torches and campfires, all of which left layers of soot on the internal walls and charcoal residues on the ground.

Using various carbon dating techniques, the study authors were able to identify the age of these different layers and provide an exquisitely detailed account of Nerja’s history.

“This has allowed us to extend the general chronological interval of the site, pushing back the origin of human occupation in Nerja cave by more than 10,000 years,” explain the researchers in their paper. In total, they identified 73 distinct phases of occupation, ranging from 41,218 to 2,998 years ago.

Based on these findings, the authors conclude that “Nerja Cave is the Palaeolithic Art cave in Europe where the greatest number of phases of distinct prehistoric visits to internal areas have been recorded.”

Along with this discovery comes new insights regarding the various ancient human cultures to have conjured up a flame within the cave.

For instance, the oldest residues identified by the researchers coincide with the Aurignacian industry, which is associated with the earliest modern humans in Europe.

It’s also possible that some of this soot was left by the torches of Neanderthals, thus providing new insights into our extinct cousins’ mastery of fire.

Further analyses revealed that a particular type of pine was used for the fires that lit the cave throughout prehistory, despite the availability of other wood sources in the nearby environment.

This suggests that subsequent waves of human occupants all identified this particular tree as the best source of fuel for their torches.

Zooming in on a single stalagmite, the researchers detected soot from 64 separate incursions spanning the latter part of the Stone Age and the Copper Age, between 8,003 and 3,299 years ago.

Based on their calculations, the authors say that the cave was visited once every 35 years throughout the Neolithic period.

While Nerja Cave continues to guard its many ancient secrets, these findings do at least help to tease out some of the details regarding the chronology of its use, as multiple generations of human visitors scrambled inside the cavern to create and observe art by the light of their pinewood torches.

Describing the ambiance inside the cave during these visits, study author María Ángeles Medina-Alcaide explained that “the prehistoric paintings were viewed in the flickering light of the flames, which could give the figures a certain sense of movement and warmth.”

The study was published in the journal Scientific Reports.