Stone Age People Used This 35,000-Year-Old Woolly Mammoth Tusk Tool to Make Rope, Scientists Say

The rope is one of the oldest human tools, and it played a crucial role in the daily lives of many ancient civilizations. Drawings found in Egyptian tombs, dating back 6,000 years, depict ropes being used to transport enormous stones utilized in pyramid construction.

However, evidence of rope usage predates even the Egyptians. Fossil fragments discovered in caves have been carbon-dated to approximately 17,000 years ago. Furthermore, around 2800 B.C., the Chinese mastered using superior hemp fibers for rope-making.

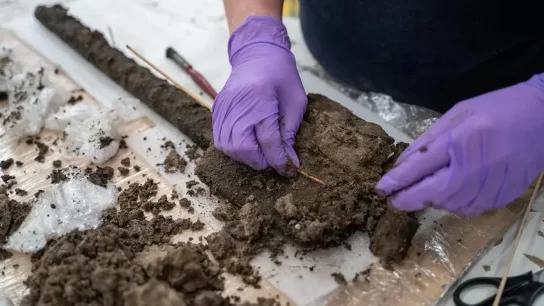

Scientists have uncovered evidence people living in central Stone Age Europe had knowledge of ropemaking. While excavating in the Hohle Fels Cave in southern Germany, archaeologists made a rare discovery.

Researchers successfully pieced together 15 fragments of mammoth ivory found at the site to construct an almost intact rope-making tool. The reconstructed implement measures approximately 20 centimeters long and is characterized by four circular holes, each intricately engraved with a spiral groove.

The Hohle Fels cave is a significant archaeological site associated with the Aurignacian culture of the Upper Paleolithic period. The e World Heritage cave Hohle Fels was excavated for the first time in 1870.

Scientists have continued to examine this important site, and the artifacts unearthed from this location are among the earliest known instances of prehistoric art and musical instruments, making them extremely valuable for our understanding of early human history.

Not so long ago, scientists recovered a fragment of a carefully carved ivory figurine that gives one of the most famous Ice Age works of art a new look.

Unique Perforated Baton

Radiocarbon dating of this remarkable mammoth ivory bone used for ropemaking shows it was turned into a tool some time between 35,000 and 40,000 years ago.

It is a legacy of Eurasia’s ancient Aurignacian culture that was marked by a great diversification and specialization of tools, including the invention of the burin, or engraving tool, that made much of the art possible.

Convex surface second from the left, flat surface far right. Distal end up, handle down.

The majority of perforated batons are crafted from reindeer antler. While there are instances of batons with multiple holes, it is more common to find them with just a single hole. The purposes of perforated batons have been debated.

Some scholars have suggested that the grooves found on these artifacts may be a result of modifications made to the holes rather than serving a specific purpose. The possibility these ancient bones were symbols of authority or ritualistic items, occasionally linked with burial practices or diverse forms of art, has also been considered.

In their study published in Science Advances, the researchers explain they decided to re-examine the mammoth ivory artifact and test the hypothesis that these meticulously crafted objects were used as functional tools rather than serving as symbolic artifacts.

The researchers were not persuaded by the suggestion that four comparable mammoth ivory artifacts discovered at other Aurignacian sites in Germany were either ritual objects or tools used for aligning wooden shafts or processing leather.

“We suspected that the holes with spiral grooves were made to have something fed through them, which led us to hypothesize that the artifact may have served to align fibers to make rope or twine. While twine can be made by hand without tools, by pulling and twisting plant fibers together, we tested whether or not the perforated baton from Hohle Fels could have been used to align, twist, and combine fibers to make rope.

We also examined how Paleolithic people could make such a precision tool and looked for use-wear and residues with the goal of determining how the object had been used,” archaeologists Nicholas Conard and Veerle Rots explain in their study.

To understand the purpose of the rare mammoth ivory tool researchers carried out experiments on rope-making using replicas of ancient four-holed tools made from various materials such as wood, animal bones, a split tooth of a warthog, and bronze.

The procedure involved threading animal sinews and five different types of plant fibers through the holes in these tools. Thin ropes that were hand-twisted were guided through these holes by one person each. Another individual held the tool while someone else twisted and pulled the emerging fiber strands to create a single piece of rope.

According to the scientists, it typically took four or five people to produce five meters of durable and flexible rope within 10 minutes using this method.

“Turning to the use of multiple holes in combination to make rope, we focused our tests mainly on cattail. We found that the Lochstab was not essential for manufacturing thin rope, which can be done manually. The tool’s relevance lies in making thicker, stronger rope consisting of two to four strands.

We twisted and fed bundles of cattail leaves through the holes. The holes help to maintain a regular thickness of the strands and facilitate the addition of new material necessary for making long stretches of rope,” the scientists write in the study.

“The discovery of what is likely an Aurignacian ropemaking tool at Hohle Fels helps to answer the question of how Upper Paleolithic people produced rope,” the researchers concluded.

The study was published in the journal Science Advances.