World’s Oldest Trousers Used Methods Still Employed by Modern Fashion

The pattern was just as detailed and strong as the modern, factory-made denim jeans. Ancient people had style.

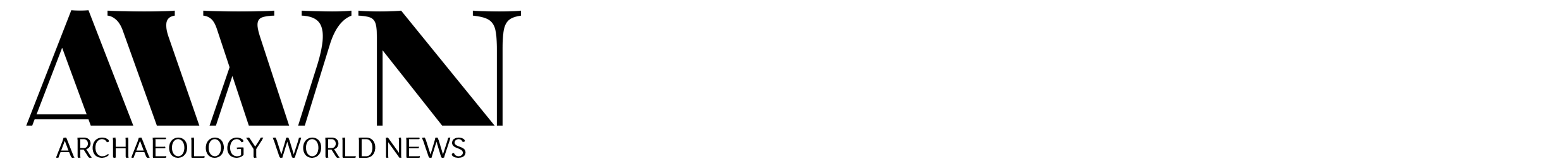

Chinese archaeologists discovered the mummified remains of 500 people who had been buried in the Yanghai cemetery in the Tarim Basin in the early 1970s.

The Tarim Basin is a large region in northwest China that has produced many significant discoveries regarding the history of ancient humans, from the remains of the earliest-known settlers to the origins of fashion.

The researchers were particularly drawn to one person since it had not only been flawlessly preserved but was also still flawlessly dressed after all this time.

The Turfan Man, so named for the nearby Chinese city of the same name, had entered the grave dressed to the nines, donning a poncho, soft leather boots, and a woolen headband embellished with bronze discs and shells.

Even compared to the Egyptian pharaohs, this mummified corpse had quite the wardrobe. The Turfan Man’s trousers, which had two tapering leg sections joined at the top by a crotch piece that appears to have given the wearer enormous mobility, were the most amazing of all. The pattern was just as detailed and strong as the modern, factory-made denim jeans.

The original cause of Fashion Week

The Turfan Man’s trousers, which have been dated to at least 3,200 years old, are thought to be the earliest pair of trousers ever found, providing experts with a general idea of when this now-essential article of clothing was initially created.

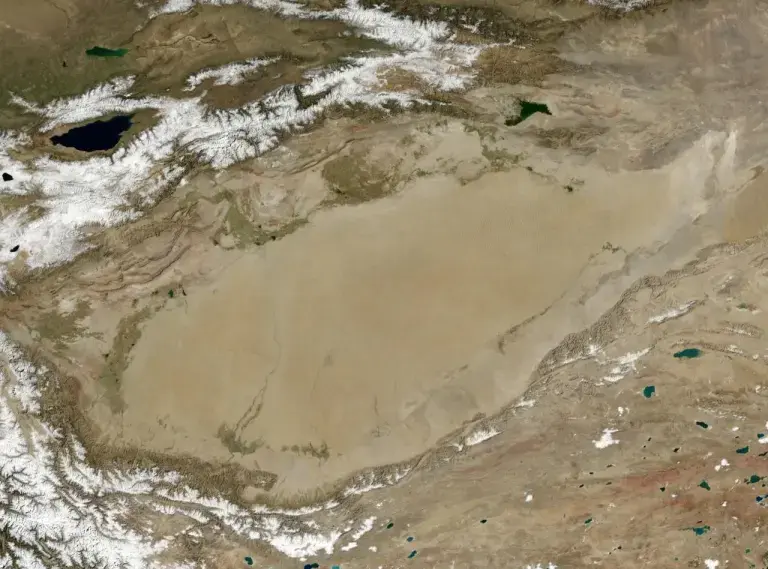

Science News states that in the past, “Europeans and Asians wore gowns, robes, tunics, togas or — as observed on the 5,300-year-old body of Ötzi the Iceman — a three-piece combination of loincloth and individual leggings.”

A significant part of human history is fashion, yet its roots and importance are frequently ignored. This is somewhat a result of our own biases. When compared to things like economics, politics, science, philosophy, or the fine arts, clothing is frequently viewed as being less significant because it is “synonymous with frivolity, excess, and luxury,” according to costume scholar Olivia Warschaw in an article on the philosophy of fashion studies.

Additionally, most fabrics don’t typically retain as well as bones do, which makes it extremely difficult for archaeologists to paint a clear image of how fashion evolved in the ancient world.

However, fashion is a cultural universal, and the development of prehistoric clothing reveals much about the similarly prehistoric people who wore it, from the concepts underlying their cultural and religious activities to their travels across different parts of the world.

Untangling the oldest pair of pants in the world through fashion studies

It turned out to be far simpler to determine when the Turfan Man’s trousers were manufactured than how they were made.

However, the atoms themselves do not tell anything about the methods or influences that ancient craftsmen used to join them together to construct a pair of pants. Carbon dating and other sorts of study can give us reasonably accurate age estimations.

The German Archaeological Institute’s Eurasia Department’s scientific director, archaeologist Mayke Wagner, put together a team of geologists, chemists, and fashion designers to investigate the Turfan Man’s rumored attire.

In order to reenact the original manufacturing procedure and unravel the garment’s greatest mysteries, their goal was to research the weaving techniques.

In the March 2022 edition of Archaeological Research in Asia, Wagner’s team discussed the results of their investigation.

They discovered, in essence, that the Turfan Man’s trousers were woven by a single machine and that up to four different weaving methods were employed by its artisans. It was discovered that two of these were exclusive to this particular pair of pants. These textiles were referred to as “Yanghai weft twining” and “Yanghai dovetailed twill tapestry.”

Wagner’s team hypothesized that the Turfan Man’s trousers were woven rather than sewn together since the fabric of the pants exhibited no traces of cutting or knitting. Their assumptions turned out to be accurate; a preliminary study of the antique clothing indicated that the trousers were constructed using the twill weave method, which is a method of weaving.

The fabric is less rigid and more elastic thanks to the twill weave type, which creates a diagonal pattern of parallel ribs, giving the wearer more mobility. This revelation is not all that shocking given that the people buried at Yanghai belonged to a society of herders and horse riders.

What is surprising, though, is that when the Turfan Man’s pants were constructed, twill weave was still a novelty. The earliest known fossil examples of twill weave, according to textile archaeologist Karina Grömer of the Natural History Museum Vienna, were found on pieces of woven cloth that were discovered in an Austrian salt mine, thousands of miles from China’s Tarim Basin. The Turfan Man’s trousers were thought to be at least 200 years younger than these textiles.

Like today’s jeans

Because twill weaving is so uncommon, significant concerns must be asked regarding the cultural influences that may or may not have influenced these early Chinese artisans. It was also evidence of their competence. The same method is used in contemporary denim jeans, which are renowned for their durability. “This is not a beginner’s item,” Grömer, who looked at the garment previously but wasn’t involved in Wagner’s study, told Science News. “It’s like the Rolls-Royce of pants,” someone said.

The fabric around the knees was woven using a separate technique called as tapestry weaving. When compared to twill weaving, tapestry weaving produces a layer of fabric that is thicker, which in this case would have protected the wearer’s joints while mounting a horse. A strong yet surprisingly flexible waistband was made using a third weaving technique on the upper border of the pants to keep them in place.

Fashion designers were able to identify the weaving patterns with ease, but they had no idea what tools the craftsmen would have used. Archaeologists have no clue what an ancient loom from this area might have looked like, and no weaving implements have ever been discovered at or close to Yanghai. Wagner speculates that the artisans might have employed a loom that could be operated while seated, but this is all conjecture.

According to Wagner’s research, their best chance is to create additional reproductions using various historic and modern weaving techniques, then identify which of these replicas is most similar to the original. The researchers hired a skilled weaver to create their duplicate, who used the same material as the ancient Chinese artisans: yarn spun from coarse-wooled sheep. Future duplicates would be made of the same material.

Putting the past back together one fiber at a time

“Clothes make the man,” as the saying goes, takes on new significance in textile archaeology. We may learn a lot about ancient civilizations, especially those without their own writing systems, by studying the methods used to make clothing and the purposes for which it was worn.

In just a few decades after his passing, mobile populations all over Eurasia were donning trousers, proving how influential The Turfan Man was in setting fashion trends.

According to other archaeological investigations, the rise in popularity of trousers and the development of horseback riding are related. Little wonder.

As previously indicated, the Turfan Man’s trousers’ twill weave and flexible crotch piece coupled a snug fit with enhanced mobility—garment attributes that are helpful when you have to climb and ride horses on a regular basis.

The crotch piece has been expertly crafted by Yanghai artisans. The Turfan Man’s crotch piece was different from other Central Asian trousers in that it was wider in the middle than it was at the ends.

Wagner’s team tested the replica on a man riding a horse bareback to better understand the purpose of the design and discovered that the trousers fit comfortably while yet allowing the rider to firmly wrap his legs around the animal.

Ancient style

The designs on the clothing can provide insight on the cultural and economic ties in the Turfan Man’s community, just as the shape of the crotch piece can provide information about his way of life.

According to Wagner’s research, ceramics from Siberia and Kazakhstan, as well as bronze containers from China, have the same interlocking T-pattern embellishing the knees.

The simultaneous emergence of this odd pattern in both Central and East Asia suggests that despite their geographical separation, the two regions were closely linked by long-term communication.

This happened at the same time as West Eurasian herders entered Asia on horses, which after domestication made it simpler to move to and from remote areas.

The stepped pyramid pattern on the Turfan Man’s trousers is similar to another pattern found on pottery from the Petrovka culture of Central Asia, which flourished between 3,900 and 3,750 years ago, as well as to the architectural styles of societies in southwestern Asia and the Middle East that date back more than 4,000 years.

The migration of Eurasian herders eastward and the potential origins of twill weaving in Eastern Europe, among other archeological findings, all point to the idea that the development of the world’s first pair of pants was the result of a cultural and economic exchange between groups of people who, up until that point in history, had hardly interacted with one another.

Because of this, anthropologist Michael Frachetti of Washington University in St. Louis has described the Turfan Man’s trousers as “an entry point for examining how the Silk Road transformed the world.” Wagner wholeheartedly concurs. Eastern Central Asia “was a laboratory where people, plants, animals, knowledge, and experiences from different directions and sources came… and were transformed,” the archaeologist told Science News.